FOIA Council subcommittee curtain-raiser, I

The council's meetings subcommittee scheduled to meet June 16 at 1 p.m.

The FOIA Council’s subcommittees on records and meetings took a hiatus last year, with the chair taking the position that attendance at the workgroup the FOIA Council was to convene on FOIA request fees was optional for council members. Members Elizabeth Bennett-Parker, Maria Everett and Lola Perkins took turns attending — thanks, ladies — but the rest of the members were off the hook.

This year, those subcommittees are not only meeting, they both have very full plates.

I’ll get to the records subcommittee in another post, but here I want to discuss the agenda of the meetings subcommittee, which meets June 16 at 1 p.m.

If you can attend the meeting, it’s in the General Assembly Building, House Room B.

If you can’t attend the meeting but have time to watch it, use this link on the day-of.

If you have thoughts on any of these issues, share them with the FOIA Council subcommittee members1: Del. Elizabeth Bennett-Parker, Maria Everett, Chidi James, Lola Perkins and Ken Reid.

The agenda bill

During the 2025 General Assembly session, Sen. Adam Ebbin carried a bill requested by VCOG that seeks to rein in the practice of adding surprise items to an agenda and acting on them without the public’s advance notice.

Though I have floated this idea in the past, the impetus for the bill was primarily the situation in Petersburg where the city council came out of a closed meeting and added an item to the agenda to scrap the RFP process by which they were evaluating bids to build a casino in the city AND to also vote on picking a contractor who hadn’t submitted a bid.

There were other recent instances, like the sudden addition in Hampton schools of an item to increase the superintendent’s salary by 50%. In Mathews County, they voted to disband the IT department in an unannounced agenda item. This spring, Norfolk schools added a resolution to the agenda at the meeting that directed staff to create a plan to close 10 schools in the district.

Citizens rely on the notice and the agenda to make decisions about whether to attend a meeting and whether to ask to comment (sometimes they have to sign up in advance to offer comment). When last-minute items are added, it thwarts part of FOIA’s policy to “afford every opportunity to citizens to witness the operations of government.”

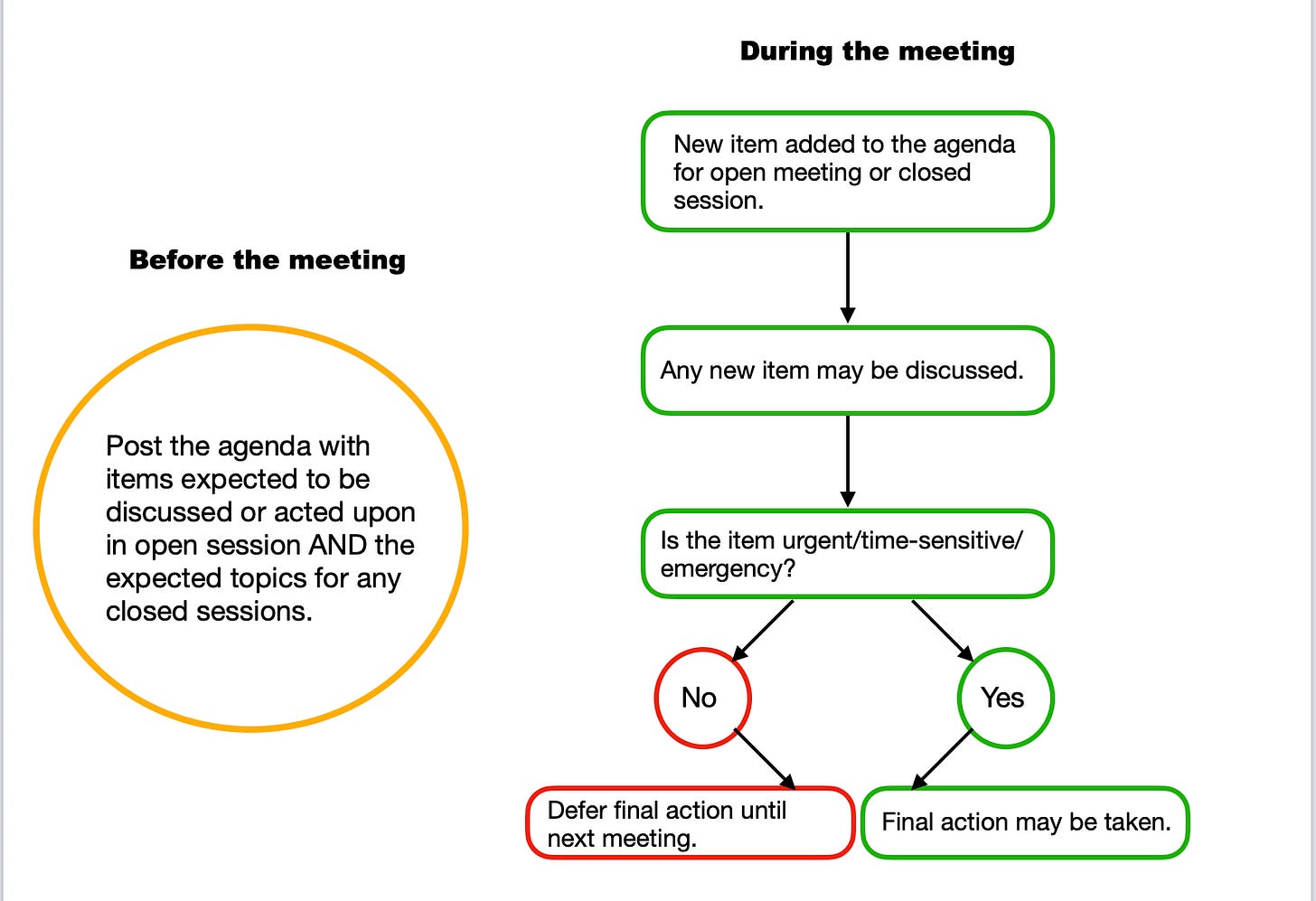

The original bill didn’t prohibit DISCUSSING matters added at the meeting, it just prohibited ACTION on those items. However, understanding that sometimes things come up unexpectedly — emergencies, deadlines — the bill was amended in the Senate to include a release valve for matters that are time-senstive.

The Virginia Municipal League, the Northern Virginia Technology Council, the Association of Regional Planners, the City of Alexandria and the Virginia Press Association agreed to the amendment. Neither the Virginia Association of Counties nor the Virginia School Boards Association spoke against it. It passed the Senate General Laws Committee 14-0. It passed the Senate Finance Committee 14-0, and it passed the entire Senate 40-0.

Once in the House, Arlington and Fairfax Counties stepped in to successfully agitate against the bill and it was sent to the FOIA Council for further study.

I’ve been a bit of a broken record on this bill (or at least the concept) because in my pea brain, it seems so easy. I even made a fancy flow chart (with “fancy” being in the eye of the beholder) to show how easy it is.

I’ve heard several arguments that there should be leeway for them to vote on matters coming out of closed session. We dealt with that in a House amendment that wasn’t ultimately adopted, but I think that as long as you include that notice on your original agenda, you’re still fine. A closed meeting agenda item shouldn’t be treated any differently from any other agenda item.

I’ve also heard arguments that there should be a distinction between important/non-important, substantive/non-substantive items. I find that approach too messy. Who and how will we define what is non-substantive? And non-substantive to whom? Should it matter if there’s broad agreement among the board members to add an item? No, because this measure is about the PUBLIC’s awareness of the matters.

No, I don’t want to tie the hands of public bodies, but I also don’t want the public to be sold a bill of goods without any prior notice.

Emergency Meetings Protocols

Long before the pandemic, Virginia implemented rules that would allow members of a public body to meet all-electronically in an emergency situation. This was before Zoom, so we were talking about conference calls, and we wanted to give elected officials a tool to talk about the emergency itself.

The pandemic forced us to rethink what is meant by an emergency, as well as what kinds of items can be discussed and acted upon at meetings during an emergency. So, in 2021, VCOG worked with others to get the law amended to allow action on a broader range of items during a declared emergency. And in 2022, VCOG led the drafting of a bill to allow occasional all-virtual meetings for non-emergency times.2

Meanwhile, members of a board can exchange emails among themselves (though a group-wide “reply all” exchange could be problematic), and they can talk one-on-one with each other until the cows come home.

In other words, to use the phrasing heard often during the legislative session, there are already a lot of tools in the toolbox for public bodies to meet and/or talk during emergencies.

A letter from the chair of the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors chair and another supervisor says those tools aren’t enough. They need to have the “ability to communicate quickly in … dire situations.”

The two dire situations they cite are (1) when a firefighter died in the line of duty, responding to a gas explosion, and (2) when a bomb threat was made at a county school. In the first case, the chair made separate phone calls to tell other supervisors to tell the public not to go to the scene. In the second case, the board was in a meeting when news of the bomb threat came in and the chair pulled each member off the dais one by one to tell them.

I’m not sure where the problem is. In both cases, it was about relaying messages to the members, which the chair can do via email. And what is it the board thinks it could do — or do differently — with more tools. What could the board do in the explosion case. Do they need to actually discuss whether to tell the public to stay away from the explosion scene? Or do they just need to know that they should tell them that. Would it be that much faster to set up and get on the Zoom call instead of just sending a text or email or calling each other one-by-one?

As for the bomb threat, again, I’m not sure what the board thinks it could do - or do differently — if only the rules were different. They’re already in the same room, they’re already in a meeting. Do they want to take a recess and talk amongst themselves? I don’t know.

And keep in mind that the threat was made against a school, and this is a board of supervisors. Sure, it’s important that the board members know about it, but isn’t it also important for the people sitting in the audience — who may have children or other loved ones in that school or who live next door to it — to know about it?

The letter has an answer for that: “[T]o ensure that public panic is avoided.” Sounds a bit like soap-opera logic to me: We must not tell Stella that I’m her birth mother so she won’t get upset with me. I’m afraid I just don’t agree that avoiding public panic a valid reason to allow members of a body to talk privately any more than they already can.

Stakeholder Meetings

It’s become quite popular over the past four or five years to add enactment clauses to legislation directing this agency or department to form a workgroup to study an issue.

The goal is laudable — get all the people who care about and are impacted by a bill into a room to talk about how to fix various problems. Legislators like them because it lets all of the stakeholders work out their issues before the legislative session, where they will hopefully present a consensus draft bill.

Workgroups, sadly, aren’t always that productive, as I learned last summer as a member of the Task Force on Transparency in Publicly Funded Animal Testing Facilities. We had facilitators, agendas, organized comments, presentations and discussions, but in the end, no bill came out of it and there was little consensus.

And, if you followed along last summer as the FOIA Council’s workgroup on fees met six times for over 12 hours, and the compromise bill seemed destined to pass, it was yanked off the House floor on one of the last days of the session.

Four years ago, legislation directed the State Council of Higher Education to come up with standards for livestreaming meetings of university governing boards. They did, and they filed a report. Only there was so little progress in imprlementing those standards that legislation was proposed this year to legislate them. The bill was amended to convene another workgroup to study basically the same issue.

Still, they’re worth a shot. The problem is with how the workgroups are created, formed and operated. The enactment clauses frequently direct the head of an agency to convene the group, and in FOIA terms, bodies created by individuals aren’t usually subject to FOIA. Still, many department heads have taken the position that the workgroups are public bodies that must follow FOIA rules.

The stakeholders are not named individually or by position but usually by affiliation, and the group is rarely exclusive or fixed. The stakeholders want to be able to meet more informally.

And it may surprise you to hear that I agree. These groups are trying to work collaboratively to fix problems and to offer legislation — legislation that will be out of their hands the minute a legislator submits the bill for consideration. The stakeholders have no power to bind anyone to anything, not even each other. The groups are usually open to anyone with an interest; no one is elected or appointed. Without these enactment clauses, there would be no question that they could get together and talk without getting tangled up in FOIA.

FOIA’s definition of public body is one that is supported wholly or principally by public funds (workgroups aren’t; no one’s getting paid by the government or taking per diem expenses). A public body can create subcommittees and workgroups of its own, and those would be subject to FOIA, but these workgroups aren’t being created by the public body to advise the public body, unlike the “advisory bodies” we hear so much about.

I’m interested to hear where this issue goes.

Pandemic Response and Preparedness

The Joint Subcommittee to Study Pandemic Response and Preparedness in the Commonwealth forwarded an issue to the FOIA Council for study: consistent, secure and verifiable voting protocols for voting and decision-making done online (e.g., counting ayes and nays during a Zoom call).

This seems like more of a technology issue than a FOIA one, but the subcommittee will at least look this over.

If you don’t have contact info for each one, you can send an email to FOIA Council and ask that your comments be distributed to the subcommittee members; the comments sent that way will also be posted on the FOIA Council website.

Keep in mind that individuals have wide latitude to call into a meeting that is otherwise happening in person. Also, state and regional bodies, as well as universities and local “advisory” boards (an undefined term) can meet all-virtually for up to 50% of their ordinary meetings.